Learning a new skill is a humbling experience. It’s valuable to feel what it’s like to be a complete beginner at something. In this post I write about my experience learning to solve the classic Rubik’s Cube, and what that has taught me about chess improvement.

During this summer, I have not spent the amount of time on chess that I had planned. Instead, I did something completely different. But somehow, it has helped my chess.

It all started in June, when my 9 year old son had bought a Rubik’s Cube. He played with it a bit, but couldn’t solve it. Neither could I. I bought a cube of my own about 20 years ago, but never learned how to solve it. I managed to get the first two layers correct, but the final layer had me beat. During the summer, my son had a friend over who solved the cube with no effort. We also visited our family in Norway, and my nephew did the same thing. So I suggested to my son that we make it a summer project to learn how to solve the cube. And so we did.

While learning the cube, I have reflected on my journey as a chess player and how I can use the lessons I’ve learned in cubing to improve my chess. And instead of keeping this to myself, I thought I’d share it with you.

First steps

It’s not enough to practice until you get it right. You need to practice until you can’t get it wrong!

Cubing, like chess, is based on very simple principles that you can learn in just a few minutes. But the more you learn, the more you realize that it’s a rabbit hole that takes you deeper and deeper. And before you know it, you’re in really deep.

The cube can be solved in different ways, but all of them require some sort of structure. When starting out, you need to learn the basics. In chess, you learn how the pieces move, and with the cube, you learn some basic patterns and how to place your fingers. After that, you are ready to learn the method for solving the entire cube.

The most efficient methods are rather complex, so it’s better to start with something simple. Like many before me, I learned the beginner method.

The beginner method consists of six steps.

Create a cross at the bottom

Insert the bottom corners

Insert the middle edges

Create a cross on top

Position top corners

Orient top corners

As the name implies, it is a simple method that only takes a few minutes to learn. However, you need to practice a number of times before it sticks. Just as in chess, it’s not enough to practice until you get it right. You need to practice until you can’t get it wrong!

Improvement gets harder when you improve

You can’t break through a plateau by doing what you’ve always done.

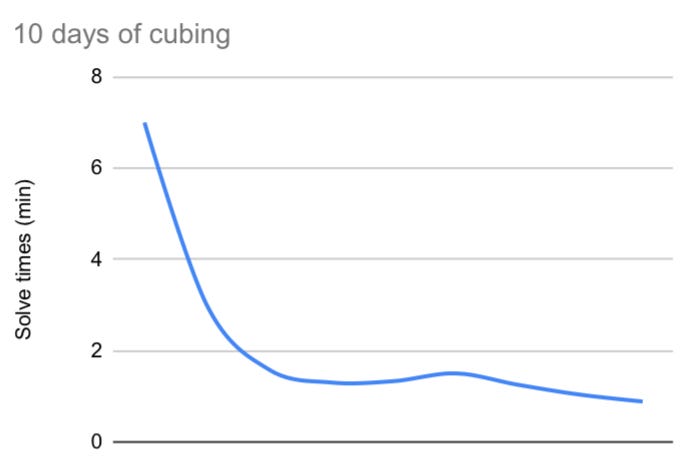

Improvement is easiest in the beginning and gets harder with time. After a few hours of practice, I did my first independent solve. It took about 7 minutes. In the course of a week, I reduced my time significantly every day, finally reaching my goal of solving the cube in under a minute.

As I got closer to the one minute mark, it got harder and harder to improve. Shaving off 30 seconds from one solve to another was no longer possible. The learning curve had flattened out, and improvement became more about the details - improving on the things I already knew.

My cubing skills had reached a plateau. And although I had reached my (initial) goal, I wanted to improve further. But you can’t break through a plateau by doing what you’ve always done. In order to get to the next level, you need to change something. I needed something else. Something more.

Reaching the next level

Learning it all is like eating an elephant; you need to take it piece by piece.

I had come about as far as I could with the beginner method, and I was now ready to move to a more advanced method, known as CFOP. The method has its name from its four steps:

Cross

First two layers (two pieces at once)

Orientation of the last layer

Permutation of the last layer

The simple fact that CFOP reduces the number of steps from six to four makes it more efficient. However, the efficiency comes at a cost; more complexity. The full CFOP method requires the application of a particular algorithm (movement pattern) for each configuration of the pieces (known as a ”case”). All in all, there are 119 different cases with corresponding algorithms (41 for the first two layers, 57 for orienting the top layer, and 21 for permutation of the last layer). This is comparable to the patterns and principles of openings, tactics, endgame and checkmate in chess. In order to reach a high level, you need to know them all. But learning it all is like eating an elephant; you need to take it piece by piece.

Luckily, there’s an intermediate version of the CFOP method in which you do the orientation and permutation in two steps each. This requires ”only'' 16 algorithms. But here’s the next problem. Switching to a new method means more uncertainty and slower times. And it’s not only about remembering the algorithms. Just as you need to recognize/understand a position in chess in order to choose the correct moves, you need to recognize the different cases (”positions”) and choose the correct method for solving each of them. This takes time and practice. So my times got worse before they got better.

Practice makes perfect?

If you want to improve, you need to identify your mistakes and work on them.

Cubing has a lot in common with chess. Both of them require logical thinking, and you need to look ahead and plan your actions. In order to do this effectively you need to know and apply different patterns. With the cube - as in chess - pattern recognition is key. You can only play what you ”see”. So exposing yourself to new patterns and ideas is a crucial component of serious improvement. You can do this by going through examples (solves/games) to acquire patterns. But (of course), only watching others solve the cube or play a chess game will only get you so far. You need to internalize the principles you’ve learned and practice applying them yourself.

It’s a skill. You need to practice! With cubing, the feedback loop is very quick - you immediately see whether or not you know a pattern. In chess, the lessons come at a slower pace. But cubing and chess share the same principle: Seeing the problem is just the first step. If you want to improve, you need to learn from your mistakes and work on the things you don’t know well enough.

Self doubt and criticism

It’s easy to be self critical. With chess and cubing alike, I am often dissatisfied with my performance. In chess, I often feel I could play a position better, and in cubing I usually feel my solves could be faster. But what I feel is a ”bad” performance now is something that used to be completely out of reach. When I solve the cube in 1 min 20 secs, I feel that I messed up. But that was my personal best only a few days ago! So it’s important to not be overly self-critical; celebrate the awesomeness you’ve achieved!

Addiction

Cubing is addictive. It’s very similar to blitz and bullet chess. Each solve only takes a couple of minutes (depending on your skill level), so it’s easy to say ”just one more” and ”OK, this is my last solve before I go to bed”. No really, this is my final one! It’s easy to get carried away.

Have you reached your maximum potential?

”Everybody” is talking about the 10 000 hour rule. But that’s what you need to become world class! You can get quite decent at something with much less than that. Studies have found that you need about 20 hrs of deliberate practice to reach a decent skill level. I started out from scratch and learned the absolut fundamentals. In just a few hours, I could solve the entire cube. And after 2 weeks of practice, I have a personal best of 38 seconds and can consistently solve the cube in just under a minute. And I’ll continue to work on it.

So it’s clear to me that it’s never too late to learn a new skill. And with just a few hours of structured practice, you can get pretty awesome! So don’t be afraid to go out there and learn something new. And enjoy the experience!

This post was inspired by a Twitter thread by fellow chess enthusiast and cuber Pascoe Rapacci. Thanks for the inspiration, buddy!

I'm enjoing chess for 4-5 years now (got in just before Queens gambit). I've just solved my first cube today. Found your post and can relate.

Thanks for sharing.